John Matthews

Professor John Matthews attended art school from the age of 14 years and has been involved as a painter for most of his life.

He was one of the first performance artists in England in the 1960s.

John has taught art at secondary school, primary school and early years. He has researched and written books about the origin of representation, expression and symbolism in human children and, more recently, in chimpanzees.

For many years John also lectured in Goldsmiths College, University of London, both in the art school and in the Faculty of Education.

He has also spent about 2o years in Singapore as Head of Visual Art in Nanyang Technological University.

Some publications:

Drawing: Developmental Trends, in Pergamon International Encyclopedia of Education (London 1988), The young child's early representation and drawing, in Blenkin, G. M. and Kelly, A. V. (eds.)The Art of Childhood and Adolescence: The Construction of Meaning (London, 1999)

Introductory text of John's conversation with Jeremy Ackerman and guests on 11th Dec 2011:

Large Glass

Thoughts about picturing

Hello. Thanks for coming. I am John Matthews. I am an artist and tonight I will tell you something about how I go about making my work.

I should tell you that I am also a writer. I have spent many years researching the origin and development of children’s art and its significance. More recently, I studied the beginnings of expression, representation and symbolism in the actions of non-human primates. (This was a small family of chimpanzees in Singapore Zoo.) This is important for you to know because it has a bearing on how you understand my art. I should add that I do not think about my research (consciously) when I make art. I leave all theoretical matters behind me when I enter the studio.

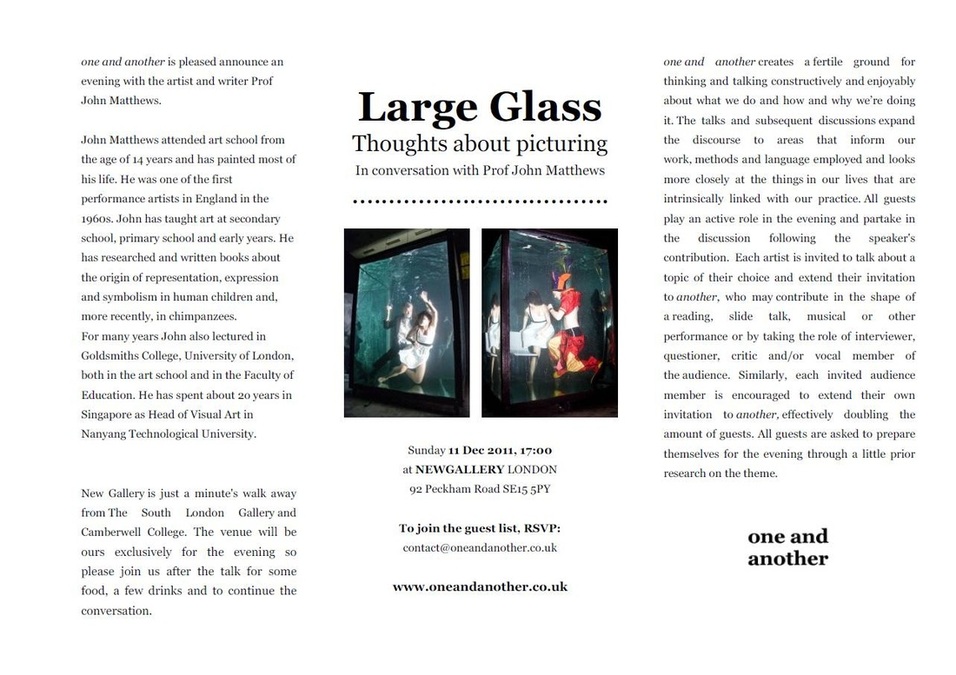

I work within a range of media and I will start by showing you a movie of a recent performance piece called “Large Glass of Water”.

(Show DVD) (5 minutes approximately including the entry into the water of Joyce Ong)

[SHOWING PERFORMANCE FOOTAGE]

I am interested in making images. This can be achieved in all sorts of media; even the best stand-up comics (for example) try to make images in the audience’s mind. I personally know this because I performed a stand-up comedy called “Sexy & Dangerous: Art Criticism in the Style of Frankie Howerd”. Incidentally, this means that an image does not have to be flat – “flatness” being an issue alluded to in the last talk in this series by the artist and poet Fabian Peake.

It’s interesting to ponder what the image is, if it is not tied to flatness. For example, is Rara the chimpanzee making an image? This is a young, female chimpanzee performing what has been called a “rain-dance”. No one knows why chimpanzees do this. These slides are from a film I made called “Dying Slave”.

(Show slides starting with Rara the chimpanzee performing a rain-dance. These slides are followed by early mark-making by a two and a half year old child (Hannah) making marks in spilt milk. As these slides are shown, I ask a similar question about whether the infant human primate is also interested in the making of an image.)

Figure 1

I have explored a range of media in my life including performance and dance. I was involved in early performance art in Britain in the mid 1960s. I am showing now examples of my work from that period to the present day (though not in chronological order).

I am deeply interested in the notion of the 2D image, composed inside the confines of the (usually rectangular) picture-surface, though at present I make use of the three-dimensionality of the paintings.

I believe my art stems from a lifelong interest in drawing, and, from drawing, then painting. I have been at art school since age 14 years and well-versed in traditional oil painting, life drawing and landscape. I was taught the rules of linear perspective. (I used to kick against this old-fashioned education but I now feel grateful to these old guys who taught me when I was a child.) I feel perfectly at home within the arbitrary limitations of the rectangular piece of paper or the canvas.

I am interested in the phenomenon of the marks, shapes and colours made on a flat plane and how these may analogue events external to the painting surface, whilst, at the same time, expressing the artist’s emotions and state of mind.

What the marks mean

How is it that these primitives of painting and drawing do this? How is it that marks, smudges and traces of paint and colour can interest me? Take (for example) one possible element of a painting, the line. A line may start off as a contour or a boundary but a moment later, at some undefined position along its route, becomes a trace of something in motion; an ephemeral abstract of time. This doesn’t happen in the real world but it can in painting. So there’s this interesting paradox that very basic aspects of reality can be set free from their usual constraints and explored as structures in themselves yet also refer to experiences beyond the painting surface.

As I have noted, I have been affected by my work with children and chimpanzees. They seem to be concerned in their art with issues of shape, location and movement. A spot or blob might mark the location of something whilst at the same time allude to its shape. When the point is in motion, a trajectory is created which moves from Point A to Point B.

This moving point may impact with another, preexisting mark, perhaps made moments, perhaps years, earlier, thus connecting present with past.

Or a mark may cross another mark, cutting through it like a blade, or “cross-out” another mark – and here I am alluding to the acts of erasure and correction. Forms superimpose each other; as occluding masses or as transparencies or veils. In my films and video-movies I have always liked superimposition and look forward with expectation to the new spaces which might emerge from it.

Little dots or blots or spots become of great interest when they seem to illustrate their own act of cascading; the spelling out of a story in the proximal and distal relations between islands in archipelagos of scattered droplets.

Again, a brush-mark or even a footprint might produce a volume (although these days I feel that treading on the canvas is rather brutal and to be avoided). However, having said this, it’s true in my work that the canvas does sometimes undergo considerable suffering from which I eventually try to rescue it.

I am intrigued by the way in which the “primitives” of painting (the marks, shapes, colours and so on) specify or allude to different spaces beyond the painting surface. For example, I like the conceits of an “up” and “down”; that something in a painting can appear to fall; as if into an abyss; as if falling forever.

The notion that one thing is “behind” another; that the layering of veils of colour create an aerial perspective, is a phenomenon I play with. I play then with the ideas of overlap and occlusion and that things and spaces may be hidden or revealed; that some things can be seen-through; they are transparent or translucent; that other things cannot quite be distinguished, or “made out”, as the English say. Hence, the idea of viewpoint is invoked.

It should be becoming clear that these basic strategies of painting and drawing, trace-making, covering and occluding, superimposing, crossing and crossing-out, hiding and revealing and so on, as well as being physical strategies which allude to physical phenomena, also have a metaphorical level too.

Yet I make no illusions. I am not interested in deceiving. I make allusions. The integrity of the surface is always preserved. The aerial perspectives allude to spaces one might feel one could step into but they always remind theviewer that they are indeed flat and only fractions of millimetres thick. This double-play, or double-knowledge, I find intriguing. It seems to point out the human condition to me.

I’ve mentioned the dot or “spot” – a small unit in space or perhaps just an indication of a position or location - a “dot on the map” (so to speak); a point in space. My father was a carpenter and joiner and as a small child I was interested in the plans he sometimes drew on his timber prior to building.

Again, my work on children’s art taught me they are dealing with issues about shape, location and movement. Perhaps the play ensembles of the apes I studied also turn upon these interests.

At this “point”, it’s worth mentioning my interest in the overlap between painting and writing. It’s sometimes rather vaguely claimed that painting is like a language (something which annoys professional linguists). In my case, however, I think I come close to making something like a language in painting. Paradoxically (perhaps), it doesn’t contain words yet it does contain sentences and stories; rhythms and patterns – a wholistic language, which pre-humans may have understood.

The canvas has thickness. In some of my work I allow thin layers (these might be thought of as glazes or veils), one over another to slowly build up the image over a long period of time. There are colours and forms which can only be made in this way. Other forms can only be configured with a fast brush, as Willem de Kooning, remarked. I think of the layers of paint as layers of time. Different epochs are put together in this way and the shades which show through the paint are like memories from a pictorial past.

Art praxis

My works involves reference to a tradition, a set of practices and understandings related to image-making. I think I am using a western art praxis which can be traced back to Renaissance Florence. It also seems to invoke a religious feeling in perhaps the recurrence of the spare and suffering figure in isolation (though I am an atheist).

This praxis is also overlaid with other influences. Apart from my research work, my time in Singapore and the Far East changed me a great deal. I was influenced by a few local artists there including Chinese dancer Lim Fei Shen and Javanese dancer Zai Kuning. Their work was performance-based, yet, because these artists came at it from their own oriental traditions, performance art became transformed from that which I had experienced in the West.

I enjoy free movement through an endless space and I think this recurs in my work. The sensation of flying through space is present in my experience of SCUBA diving and also in my practice as a tai chi player.

Although I am always drawing from something (either in the physical visual world or in my own interior one) the structures I make do not attempt to copy anything in the world; the lines I make are not reliant upon linear derivatives or shapes in the external world; are realistic only in the ipsative sense that they cohere in their own terms; in terms of their interrelationships within a visual structure. Additionally, this all has to be genuinely felt by me as I produce it. I don’t believe the feeling can be faked.

Starting work

Sometimes I start from an idea (say, a figure in a landscape); sometimes from life, from direct observation; sometimes from an accident. The accident is sacred to me because it forces me to adapt and carry on. I am interested in the discarded; the unwanted (hence, the invention of collage forms another important part of my work as well as harking again to a metaphorical level of meaning). Sometimes I paint from despair, flinging down lines and shapes and just hoping for the best. I use a kind of faith here which comes from experience; knowing that if one persists, one will eventually find form and space.

In the act of painting, everything comes down to the pressure-changing, fluctuating degrees of stress on the moving point (the brush, the pencil, mouse, stylus or whatever) and the speed with which the mark is made in response to an internalised idea of something; of a space, of a figure in space; sometimes tumbling through a strange and wonderful universe, sometimes stumbling through a wasteland like a Samuel Becket figure.

It’s important to understand that the act of “mark-making” (and there is debate about whether this is the best term) involves the reciprocal act of looking; they are entwined together cyclically and guide subsequent actions. Merely making any old kind of marking action is not what I am about. It is all guided by looking and thinking.

Both physical things and ideas hang like threads sometimes on the painting and these are very fragile and hard to preserve. This makes my work hard to exhibit. At present I make use of the three-dimensionality of painting. For example, a painting may be curled into a fold in space and turned back on itself.The fold is as much a metaphor as a physical event; the fold in a continuum of space and time is represented over and over again in Baroque art. (Perhaps my work is a kind of crumbling Baroque.)

The paintings are sometimes creased, twisted, skewed, turned upside-down or reversed. Remember that canvas has a thickness; is three-dimensional and allows the biography of the painting to show through; earlier layers glimpsed within the weave of the canvas.

How the paint is put on or applied various enormously. In fact, much of my mature painting is not strictly speaking “applied” at all, in the narrow sense of the transportation of paint from Point A, the brush, to Point B, the stable painting surface. How the paint ends up on the canvas involves a constellation of techniques I have learned over the years. I often challenge the idea of a firm and stable flat surface (perhaps an extreme example is my work underwater on plastic sheets); rather, the canvas (or paper or whatever) works in collaboration with the paint-loaded brush, absorbing or taking the pigment from it. Painting on the raw canvas gives me the kind of instability I require. At the moment, I seem to be constructing a very balanced structures but structures which are seriously threatened by imbalance.

I mentioned collage. Sometimes, as I work, two different works get associated or even physically stuck together, offering me a new space. Sometimes, it may mean that an earlier painting or a fragment of an earlier painting becomes entombed and is lost forever.

This may change. I used to always want the canvas to be immaculately stretched, so that it was completely flat and so that the image would be set free from the sculptural and tactile properties left from the act of making. By stretching them I make them less three-dimensional which “releases”, as it were, the visual image. I feel that I will return to stretching the canvases soon.

Working in this way, in tune with the natural behaviour of pigments, allowing the different ways in which one can read and reread space, the different ways in which one can fit it all together, I make the paintings.

I’m finding now the basic elements or (better) primitives of visual expression, representation and symbolism. I think, with the better paintings, although they are spare and austere they can nevertheless be enjoyed as spaces to come to rest in. You should be able to allow your eye to totally rest upon the structure made for it and let the picture or painting take over. This does require just a little effort on your part. Your eye should be able to rest on it and investigate it as a visual structure. The internal relationships between marks, spots, lines, blobs, shapes and colours should allow this. From here, you should be able to let go and go into the painting. You’ll always be reminded however about how this spatial experience is made; physical evidence remains as traces of handiwork.

The human figure

About the human figure in my work: There is one figure inside another inside another. I have been drawing and painting the human figure since I was a child. I may have produced several thousand drawings of the human figure and it is now a part of me. If I let go and just draw, the bare elements and proportions of the human figure seem to appear on the painting surface as if dropped from the brush. I think they are “figures”, rather than “nudes” because they derive from a certain tradition (peculiar to the Western world) about the figure as a construction which only really exists on the drawing surface.

Many of the paintings refer to relationships in the real world and to ideas about weight, mass and balance. Hence, in some paintings, you might find an echo of the contra-posture of the Renaissance figure. The human figure is still, yet dynamic, as if in the transition between 2 poses. Sometimes the figure appears to be at the moment of toppling yet we know that an instant later – in an (as yet) un-depicted future moment - the struggling hero or heroine has a possibility to regain his or her footing. Hence, because of the reference to movement through a physical, 1G gravity field, the painting allows time to be present. The idea of the key moment, I think, is important here.

But what it is which actually constitutes the “moment”, whether it is in the movement of a brush, or the actions made underwater, holding one’s breath, when the smallest task becomes monumental, is perhaps what my art is ultimately about.

Thank you.

John Matthews

11 December 2011

Notes* bng the distortion of glass – the idea that there is no true image – also, water where it shouldn’t be – ege the Titanic popular

Language of Milton terrific pandemonium padlock The Chilterns Goats have hair not fur (which is oily) (so feel the cold)